In an interesting 10-year anniversary article, @PIrelandatBC and Darko Oračić argue that the Great Recession "was not the inevitable consequence of unstable asset markets but followed, instead, from a series of unfortunate government policy mistakes." https://t.co/lCImVS0VkQ— John B. Taylor (@EconomicsOne) May 12, 2018

But, alas, would that it were so. The article does get something right: "the Great Recession was not the inevitable consequence of unstable asset markets but followed, instead, from a series of unfortunate government policy mistakes."

But, of course, the first mistake they identify is that the Fed caused the housing bubble through loose monetary policy. Now, one problem with this, as the authors point out, is:

Some economists question this interpretation of the data, arguing that the short-term interest rates under the Fed’s control have little connection to the longer-term mortgages that finance the purchase of new homes. A 2010 New York Fed working paper, however, explains that banks and other mortgage providers borrow funds on a short-term basis to make longer-term loans. Their activities open a channel through which policy-induced movements in short-term rates strongly affect the profitability of lending and thereby affect the mortgage and housing markets.This leads to another problem, because the Fed was raising rates in 2004 and 2005 when the housing bubble peaked. In order to solve this problem, the authors lag short term interest rates. So, for instance, in a graph of home price changes compared to the Fed Funds rate, they lag the Fed Funds rate by two years. So, the low Fed Funds rate in 2003 correlates with home prices in Phoenix in 2005 rising by 40%.

I can sort of meet the authors halfway here. This is probably the most striking event that is visible in the moving chart I posted here. Some combination of flexible mortgage credit markets, accommodative monetary policy, and real economic growth, fed a boom in Los Angeles housing markets in 2003 and early 2004. Then, watching this in time-lapse, we can see that very soon after the Fed began raising rates in 2004, there was a sharp downshift in Los Angeles housing markets and a very sharp upshift in the Phoenix market. This coincided with a massive migration event into Phoenix.

You can really see in this moving chart how the Phoenix and Los Angeles markets became tethered to a single extreme causal thread. So, maybe some of that LA boom in 2003 was related to monetary policy. And, maybe the pressure on the LA housing market that grew out of that boom was related to the 2005 Phoenix bubble. But the factor that pulls those markets together isn't that there was an oversupply of housing or an unsustainable pop in real residential investment. The cause was that there can't be a sustainable growth in Los Angeles residential investment.

The bubble in 2005, as is strikingly clear in this moving chart, was caused by a massive movement down-market from expensive LA homes to less expensive Phoenix homes. By the end of 2005, the Fed had tightened enough that the entire national market drops together like a bag of bricks. Watching this chart move, you really can almost feel your stomache rise at the beginning of 2006 like you're on a roller coaster drop. So, to the extent that accommodative monetary policy in 2003 was a factor in rising prices in 2005, the rising rates in 2004 were a factor in the drop that began in 2006.

So, if monetary policy works with a two year lag, then it was too tight by 2004 or 2005. I'm willing to accept that there really isn't a lag, and that it was too tight by 2006.

The article includes the following chart, using a 1-year lag in the Fed Funds rate to support the statement that: "Other statistical indicators of housing-sector activity display strikingly strong correlations with the federal funds rate. The first figure below shows that rapid growth in residential investment over the period from 2003 through 2005 was preceded by very low settings for the federal funds rate."

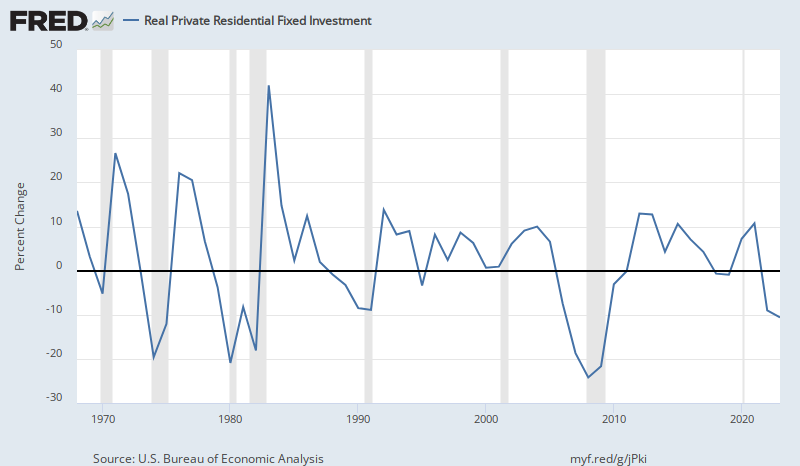

Their chart only goes back to 2000. I have added a Fred chart of annual growth in real residential investment, back to 1967.

Their chart only goes back to 2000. I have added a Fred chart of annual growth in real residential investment, back to 1967.The idea that loose monetary policy created a housing bubble is entirely dependent on high prices. And high prices were entirely dependent on the lack of real residential investment in specific localities.

So, the irony is that there is a dual claim here, involving public policy errors.

|

| Add caption |

and

2) The Fed erred by being too tight after the housing market collapsed.

The irony is that the second claim is absolutely correct, and that the reason the second claim came to be true is because so many people falsely believed claim number 1.

And, the problem is that it is claim number 1 that seems to motivate so much of the policy debate. Claim number 1 is certainly the primary influence on public policy for the past decade.

It would be really nice if economists in general found something more useful to worry about than having too much real investment.

I dont see how you can conclude the Fed was too tight given what was known at the time. CPI was >3% most of 2004-2008 and peaked well over 5%. If the Fed hadn't tightened who's to say inflation wouldn't have peaked at 10% and resulted in even higher rates? We don't know the counterfactual. The Fed acted appropriately given what (at the time) appeared to be a fairly significant inflation problem.

ReplyDeleteThis isn't a question of too-easy vs too-tight. It's a problem with the fundamental way our economy works. It seems that to generate growth near potential we need to add massive amounts of leverage to the system. Where that takes place each cycle may change, but it seems to be a feature. Then you have an inevitable lag between central bank easing and inflation so the central bank ends up behind the curve. Leverage+above-target-inflation is a toxic combination.

For those who think NGDP targeting is the answer i fully disagree. If you use trailing NGDP as our target we have the same problem with CPI (backward-looking). If we were to try to get an unbiased market estimate, it would be highly correlated with forward-inflation measures (which we already have) so there is no new information content from switching to NGDP.

A forward NGDP target would be better, just as forward inflation signals in 2008 were better signals than trailing measures.

DeleteI would say that the NGDP signal was marginally recessionary as early as late 2006. Following an NGDP target, the Fed would have introduced some accommodation as early as 2006.

The urban housing supply problem that I have been covering increases debt levels, inflation measures, lowers real growth, and i think even caused the rise in unemployment to be delayed in 2007. The problems caused by obstacles to urban growth are being blamed on the Fed.

I agree that using forward-looking measures would help a bit. But not much. 10y inflation expectations didn't dip below 2% until September 2008. And didn't dip below 1.5% until October. Maybe you would have gotten one extra rate cut if the Fed were watching that.

DeleteThere is another giant problem with market measures that no one wants to addressed. They could be profitably gamed. When you have a fairly small market influencing monetary policy, which influences enormous markets - people will find a way to game it. It could easily make monetary policy less accurate than it is currently.

Agree fully on housing supply. That's the big problem here. Not much a central bank can do about it. It's a negative supply shock and they have to treat it accordingly (at least until a point in time when it appears the country is willing to get serious about it - good luck).

The orthodox macroeconomics profession will not place urban property zoning into the macroeconomic context. This leads to strange outcomes such as Robert Schiller publicly wondering why house prices are so high, even globally.

ReplyDeleteAdd this blind spot to an inability to wrestle with the positives or negatives of quantitative easing and you have a macroeconomics profession that is not addressing the main issues of the day in their own sphere.

NGDP was dropping while inflation was level. It was a warning sign. But I wonder how much higher house prices in LA would be now if there was no tightening. But at least the middle class would hold the wealth. The tightening was by the rich and for the rich to dominate lucrative housing markets. It was a conspiracy to fleece the average homeowner and it worked.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much Dr Lucky for bringing my life back, i never thought i would ever be cured of HSV1 again due to the medical report i had from the hospital not until When God used Dr Lucky herbs and root in curing me of HSV1. Contact his on Email; drluckyherbalcure@gmail.com or WhatsApp him; +2348154637647

ReplyDelete