New York property jitters herald declines elsewhereThe first line:

Clouds are hovering over New York’s housing market.

This is a great example of the mass hypnosis that has infected the public consensus on housing.

There is a broadening realization that the lack of access to urban labor markets and the lack of access to affordable urban housing are the prime challenge of early 21st century economics. The problem is, solving that problem requires economic dislocation and upheaval of urban housing markets. If you see falling real estate prices in urban centers should your reaction be to worry about "clouds hovering" over urban real estate markets? I say, celebrate.

If our primary economic problem is that a lack of housing in urban centers causes it to be overpriced by a factor of 2 or more, then the DIRECT solution to that problem is that urban real estate needs to lose 50% or more of its value. This article begins by noting that the median price per square foot in New York City has declined by 18% from last year. Your reaction to that should be, "That's a great start!" Full stop. If that's not your reaction, then what are you doing? What's your purpose?

Further, the article argues that global capital markets are leading to a new synchronization of urban real estate markets, so that additional supply is such a strong factor in bringing down urban housing costs that new units in New York City can bring down prices in London. Your reaction to that should be, "Wonderful news! Supply is a much more powerful factor than we thought." Full stop. If that's not your reaction, then what are you doing? What's your purpose?

Reasons given in the article for this drop in New York prices include: (1) removal of tax benefits, (2) "glut" of luxury supply, (3) globalization, (4) "financialization", (5) "ultra-loose" money. Your reaction to that should be, "Oh. OK. Those must all be good things. Let's do more of those things." Full stop. If that's not your reaction, then what are you doing? What's your purpose?

But, that's not the direction the article takes. The article notes that sales volume is also down, and, as is the convention, it treats this downturn as the inevitable end of a boom bust cycle. So, instead of seeing the drop in sales as a sign that all these good things might come to an end - as something we should counter - the article treats the boom that preceded it as the problem, and the solutions proposed are all policies aimed at stopping the real estate expansion before it develops!

This is an explicit defense of a monetary and credit regime that is specified to ensure rising urban real estate costs.

Now, admittedly the problem of solving urban costs is difficult, because normalized, unconstrained urban housing markets would require building with few unnecessary obstructions and low costs. And, part of what happens in these regimes is that the bridge between basic costs and market value gets filled with all sorts of "limited access" rent seeking. Developer fees, concessions to advocacy and neighborhood groups and municipal powers, queuing, etc. These added costs emerged. They didn't develop as some sort of plan. So, if supply actually starts to increase enough to bring rents down to a reasonable level, these extra costs will have to be reduced in order to allow new development to come online profitably. Since the cost of queuing is pure waste, the first step here is "easy". Just keep pushing through more projects for approval that are bringing in those "clouds". There are a few trillion reasons why local planning boards aren't going to do that to existing owners and developers.

But, for activists and researchers who want to solve the urban housing problem and for global financial journalists who cover these markets, the reaction to that political problem should not be to kill any booms in their infancy. The reaction should be, "How do we entice these urban planning departments to keep pushing through new supply when it looks like a downturn is coming?" Because, to refer to any supply in these cities as anywhere close to a "glut" is a laugh. A horrible, dark, depressing laugh. There will be a glut of supply when rent in New York City is similar to rent in Atlanta, or even Chicago. Until then, any use of the word "glut" to describe New York City housing should be met with laughter.

The reason we are engaged in this odd public rhetorical house of mirrors is because we all have a virus in our brain. It's a cultural meme. And it's a received canonical premise that there was a housing bubble, and that bubble was caused by loose money and loose credit.

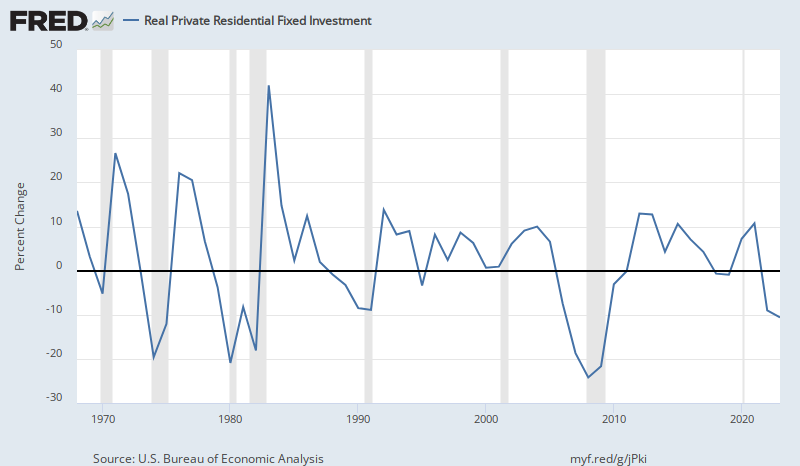

The housing bubble, such that it was, was caused by an extreme shortage of urban supply. Because of that shortage of supply, the process of meeting the public need for housing requires a "bubble" and the availability of credit that is flexible enough to allow for ownership where rents regularly take 50% or more of a household's budget. Since supply in those cities barely responds to price, prices in those cities have to be bid up to high enough levels to induce outmigration so that new housing can be built in the rest of the country where supply can react to high prices and high demand. At the peak of the US housing "bubble", credit markets were just beginning to push market prices to a level that induced that new supply.

Now, it would be better to build ample units in the urban centers. But, since that doesn't appear to be close to happening, this was a second-best solution. And, in terms of rent - which is the appropriate measure for considering housing affordability - 2005, briefly, was the one point since 1995 where supply at the national level was abundant enough to moderate rising rents.

Now, it would be better to build ample units in the urban centers. But, since that doesn't appear to be close to happening, this was a second-best solution. And, in terms of rent - which is the appropriate measure for considering housing affordability - 2005, briefly, was the one point since 1995 where supply at the national level was abundant enough to moderate rising rents.Unfortunately, the Closed Access cities in the US are such a problem that in order to create enough housing at the national level, we had to induce a mass migration event out of those cities, and that mass migration event was the source of the dislocations in places like Phoenix that drove the country to demand a credit and monetary contraction.

This is the first step to fixing the problem. We need to get that virus out of our heads. The problem, all along, was supply. Trying to pop the bubble before it inflates is the opposite of what we need to do. I think the first rhetorical step to beat this virus is to stop thinking about housing affordability and housing markets in terms of price. Price is a secondary function. Affordability is about rent. And, in the end, price is also about rent. And, in the past 25 years, there have been two successful means for moderating rents. (1) build like it's 2005, or (2) pull back on the money supply and credit so severely that a good portion of the country is foreclosed upon.

If we had committed to (1), today rents would be lower, prices would be higher, homeownership would be strong, and American balance sheets would be healthy. It would be nice if a lot more of those American households could also live in the coastal cities. I don't know if that can happen, but it sure as heck isn't going to happen if there is a consensus reaction to protect those precious urban real estate values every time the solution actually starts to play out by worrying about a "glut" of supply, and then by accepting pro-cyclical credit and monetary policies in order to "pop" the "bubble".

In that counterfactual, where the urban supply problem isn't solved and the rest of us commit to abundant supply, there would be gnashing of teeth about how the Federal Reserve is feeding bubbles and they are at fault for making home prices too high. We have indulged that intuition for a decade now. Now we know how wrong that is. This was the darkest timeline. Let's roll the dice again and proceed with the knowledge that doing it wrong has provided us.

New York real estate is getting cheaper and is pulling housing costs down in other cities, says the Financial Times, because (1) removal of tax benefits, (2) "glut" of luxury supply, (3) globalization, (4) "financialization", (5) "ultra-loose" money. OK. Those must all be good things. Let's do more of those things. What's your purpose?