There are so many ways in which we were tricked by our very own eyes and our very strong biases toward coming to pre-ordained conclusions about the housing boom. Generally, these biases led us to blame lenders and speculators when prices were rising sharply. One way our predispositions seemed to be confirmed was the appearance of a hot mortgage market in the midst of the boom.

Now, I like to make the point that any context with rising prices, for any reason, is bound to have a hot lending market. You can always put obstacles in the lending market, which is what we have done since 2007, to keep prices lower, but this is different than pushing prices up through lending. It is easy to see how a household who is obstructed from credit will not create demand for homeownership (although, they will still create demand for housing). But, if access to credit creates unsustainable or irrational demand that pushes prices too high, we should expect this to lead to some mitigating factors - the natural drop of demand among buyers who see the market as too expensive, the natural decision of current owners to exit the market, etc. There might be some positive feedback mechanisms from loose lending that cause demand to shift up, so that there is some level of positive feedback in hot markets, but it seems to me that the data says these mechanisms have been overstated, and they certainly weren't causal. In other words, the case for tight lending causing prices to retreat below a sort of non-arbitrage price level is easier to make than the case for loose lending causing prices to rise above a reasonable estimate of a non-arbitrage price level.

One reason that credit seemed important was that mortgage debt was rising during the period. But, according to the Survey of Consumer Finances, the typical mortgaged homeowner had leverage that was declining during the boom, and was only slightly higher than the pre-bubble level even after the bust. (This is probably due to owners overestimating their home values during the bust, in part.) It appears that leverage was mostly rising during the boom because there were fewer households who were unencumbered.

This doesn't quite match the conventional wisdom, because we imagine the housing ATM to mostly apply to households who had Loan To Value (LTV) levels of, say, 80%, getting home equity loans and moving their LTV to 90% or 100%. It doesn't really make sense that the housing ATM would mainly lead to some households taking on mortgages who didn't have any to begin with.

What I have found is that first time homeownership was probably slightly elevated from the mid-nineties on (though the financial character of buyers did not change much throughout the bubble, and if anything was strengthening). This led to rising homeownership, which peaked in 2004. From then until 2006 or 2007, the trend reversal in ownership was coming from a rise in permanent sellers - owners exiting ownership. Then, in 2006 and 2007, the collapse of the mortgage market and public policy pressures against marginal lending caused first time buyers to fall. Selling pressure remained strong, and homeownership rates really began to collapse as we now had weak entry and strong exit rates into homeownership.

So, in that 2004-2007 period - the subprime boom period - I think the primary influence on leverage was not the housing ATM factor, but this shift in ownership - a slightly strong first time buyer market (though no stronger than it had been for a decade) and a strong sellers market. The sellers tended to be long term, unencumbered owners. So, there was a tradeoff of owners without a mortgage selling to first time homebuyers who were leveraged, just as first time buyers have generally always been leveraged in the modern US housing market. The stability in leverage levels, which then began to shoot up when prices stabilized and began to decline, was from a shift in owner composition.

We can see this in the SCF measures of homeownership, both with and without a mortgage.

Looking across all families, mortgaged ownership increased by about 8% from 1995 to 2007, but total ownership only increased by about 4%. (Note that the collapse of the credit market lagged the outflow of owners. From 2004 to 2007, mortgaged ownership increased by just under 1% while unmortgaged ownership fell by more than 1%, leading to a net decline in ownership during the private securitization boom.)

Notice how there is a rise in mortgaged ownership across incomes, but this only led to a rise in total ownership in the top 60%. That 4% fall in unmortgaged ownership seems to cross income levels. It is matched by a 4% increase in mortgaged ownership in the bottom quintiles, that leaves ownership flat, and in the middle and higher incomes, mortgaged ownership increased by more like 10%, leading to a net increase in total ownership.

In the lower quintiles, the rise in mortgaged ownership was entirely offset by a fall in unmortgaged ownership. This suggests the possibility that at least part of the story was a rise in low income lending which is hidden in the aggregate numbers by an outflow of former low income owners.

But, if we look at ownership by age, I don't think this bears out in a significant way. Rising mortgaged ownership is highly correlated with age. And, ownership in the lower two income quintiles are also highly weighted to older age groups. The rising mortgaged ownership in the lower quintiles must be coming mostly from the use of leverage among lightly encumbered older, long term owners. (By the way, the length of tenure for owners in the bottom quintiles, especially in Closed Access cities is very high - typically over 20 years.) And young owners are largely in the high income quintiles, so the rise in mortgages to younger age groups must have been mostly to buyers with high incomes.

So, that rise in mortgaged ownership among the low income quintiles is a bit of a mystery. What was causing so many older owners to retain mortgages? Was it just a cultural shift with baby boomers? Products like reverse mortgages?

As you might suspect, I think migration in and out of Closed Access is an important factor here. ACS data which has details and statistical power regarding these issues only goes back to 2005. The migration patterns in 2005 were very strong, but while their scale was unusual, the direction of the trends should be similar to what had been happening for a decade. We might assume that ownership patterns in Closed Access cities in the mid-1990s were much closer to the ownership patterns we see in the rest of the country, and that the sharp differences that have developed since then are largely the product of the cost-based segregation that has developed. (Although, this isn't borne out by state-level ownership rates, which seem to have been below the national average in California and Massachusetts for some time, so maybe my intuition fails me here.)

Among mortgaged homeowners, in the massive outflows that were happening in 2005 and 2006, what we see is a sharp net outflow of households that were young and households that had low incomes. For the general population of Closed Access MSAs, the bottom 60% of households were moving away, on net, at a rate of about 2% a year, at the height of the bubble. But, for homeowners, it was more like 3%. Keep in mind, middle class and poor households don't tend to own homes in Closed Access cities, so in absolute numbers, this is a small portion of the total population of migrants. But, it gives us a window into these shifting ownership patterns.

Let's take a look at ownership patterns at the top income quintile and the 2nd quintile. Here, the orange bars are Contagion cities, the red bars are Closed Access cities, and the green bars are everywhere else. The dark bars are 2005, the light bars are 2014, the solid bars are mortgaged and the striped bars are unmortgaged owners.

Notice, in the top income quintile, ownership in Closed Access cities is similar to other cities. At the top end, Closed Access residents have to make some compromises, regarding the size of the unit, etc. But, in terms of budget and ownership status, their spending and ownership patterns are maintained. As we move down the age groups, Closed Access ownership declines, because the older owners were more likely to buy their homes before the bubble, and younger households have been priced out for 20 years. Also, note how sharply mortgaged ownership has collapsed for younger households in the highest income quintile.*

Now, look at the 2nd income quintile. This is a different story. Ownership among older households is still fairly similar across cities. These are generally households that have owned homes for a long time. But for working age households, now there is a sharp difference between Closed Access and other cities. Among younger households with moderately low incomes, ownership in Closed Access cities is negligible. Across working age groups, it runs 20% or more less than in other cities.

There would be a natural reaction from existing owners to rising prices in constrained cities to capture those capital gains, partly through selling and moving, and partly through taking out mortgage debt. The migration and ownership data suggest that selling is a significant factor. Where capital gains would be caused by supply issues, of course they would be captured in a number of ways, some of which include using the home for collateral. As we move down the age and the income distribution, Closed Access ownership, both mortgaged and not mortgaged, falls farther below the levels we see in other places. This suggests that, on net, supply pressures have a sharp effect on the quantity demanded of homeownership. To the extent that there is a notion about the bubble that expanding credit creates its own demand, pushing prices into an ever-climbing spiral, that appears to be a broad overstatement. In terms of quantity, it seems clear that among existing owners, a city with rising prices will have lower demand for housing units than a city with stable prices, even as some of those households capture their capital gains through home equity borrowing.

My shorthand for the housing bubble in the Closed Access cities is that non-conventional loans weren't putting middle income and poor households in homes; they were facilitating the sale of homes from wealthy old homeowners to high income young buyers. But, looking at SCF national data that goes back to the 1990s or AHS data on cities that goes back to about 2000, there isn't an obvious shift in ownership patterns.** There certainly isn't any shift that is a counterpoint to the sharp downward shift we have seen in young, high income homeownership in Closed Access cities since the bust.

In the end, I don't think there was a shift. There was a slight increase in ownership among the young, nationwide, but there was nothing peculiar about what was happening in the Closed Access cities - the "bubble cities". The non-conventional loans were simply facilitating the same sorts of purchases from the same types of demographic groups that had always bought homes. To the extent that they were critical in facilitating rising prices, they were allowing normal transactions at price points that had reached levels too high for conventional loans to handle. They were simply accelerating the normal process of in and out migration from Closed Access cities. The slight drop in Closed Access population during the boom appears to be about half-explained by the difference in family size between small families that move in and larger families that move out. Thus, the migration acceleration led to population decline.

* Consider what this tells us regarding causality. If creative financing caused the bubble, then when those mortgage markets collapsed, we should have seen prices falling and ownership remaining fairly level for high income groups. Instead, Closed Access ownership among high income young households has collapsed. The reason it has collapsed is because high prices are caused by supply constraints which push rents up. Housing expenses in those cities take a large chunk of any household's budget - even a household in the top income quintile. Supply constraints caused local housing costs to rise above the norms we use for conventional mortgages. Creative mortgage terms were allowing high income buyers to purchase homes outside the norms of conventional mortgages, which is the only way to purchase a home in Closed Access cities. Young, high income homeownership has collapsed in Closed Access cities, in spite of some retraction in prices, especially in lower tiers of the market, because creative mortgages weren't creating the price problem; they were just facilitating ownership in cities that had high costs. Now we have imposed constraints on creative financing, so young households with six-figure incomes are trapped in the renter's market and prices are too low to entice the remaining long-tenured owners to sell.

** Upon review, I think I made an error here. The income quintiles I use are based on national quintiles. The bottom two quintiles in the Closed Access cities only amount to about 16% of Closed Access population each and the top quintile amounts to about 30% of Closed Access population. If both renters are owners are leaving, the relative number of low quintile owners could be declining even if the homeownership rate for those quintiles isn't falling that much. So, the homeownership rate in the Closed Access cities could have risen during the boom because of changing composition to more high income households, even if the rate within each quintile, as I have defined them, remains fairly level or declines slightly. So, my shorthand would be true, even with the homeownership rate data that we see. In fact, this should have been obvious to me as a product of thinking about these things through the lens of national income segregation.

Thursday, March 30, 2017

Wednesday, March 29, 2017

Housing: Part 215 - Ownership in Closed and Open Access

Here is a chart of homeownership rates in 2007 and 2014 in Closed Access MSAs and in Open Access areas (here, defined as all areas outside Closed Access and Contagion MSAs).*

Remember, the Closed Access cities are the cities where prices are much higher than any other city and where prices rose more sharply than any other cities during the boom. They also are the only cities where low priced homes systematically appreciated more than high priced homes.**

The housing boom is widely attributed to credit extended to marginal households, so much so that "subprime bubble" and "housing bubble" are sometimes used interchangeably.

Here, I am comparing Open and Closed Access ownership patterns as well as changes over time, from 2007 to 2014. Notice, in the Closed Access cities, middle and lower class households with mortgages owned about 9% of the housing stock. This is the portion of the population that was supposedly driving prices up. All mortgaged owner-occupiers only accounted for about 36% of Closed Access housing units. Even in other parts of the country they only accounted for about 42% of housing units. The difference is that in Closed Access cities, mortgaged homeowners overwhelmingly come from the top end of the income distribution.

It is implausible that working age, middle or lower income households were associated with significant pressures pushing Closed Access prices up. Non-conventional mortgages in Closed Access cities had to be focused on young households with high incomes.

In 2007, just under 9% and 17% of Closed and Open Access housing units were owned by households in the bottom 60% of incomes. By 2014, these numbers had dropped to just under 7% and 14%. So, about a quarter of the pool of working age, middle and lower class mortgaged homeowners had dried up since 2007. Homeownership rates have continued to fall since then.

In many ways, homeownership has collapsed much more than aggregate numbers would suggest. In Closed Access cities, mortgaged ownership is down to 30% of all households (from 36%). In Open Access areas, it's down to 34% (from 42%). In Open Access areas, about 40% of homeownership was unencumbered in 2007. By 2014, nearly half of owner-occupiers were unencumbered.

Total homeownership rates have been stabilized because unencumbered owners or lightly encumbered owners were not hurt as badly by falling equity and have been more likely to keep their homes. Mortgaged ownership has been devastated, both because existing owners were foreclosed on and because many potential new owners are locked out of the market.

* Contagion ownership patterns tend to be similar to Open Access ownership patterns.

**The systematic relative increase of low priced homes also began to appear in Washington, DC, Riverside, CA, and Miami by the end of the boom, because prices in their high end zip codes were rising above $500,000 where further home price appreciation slows down compared to lower price levels. This has nothing to do with credit access.

Remember, the Closed Access cities are the cities where prices are much higher than any other city and where prices rose more sharply than any other cities during the boom. They also are the only cities where low priced homes systematically appreciated more than high priced homes.**

The housing boom is widely attributed to credit extended to marginal households, so much so that "subprime bubble" and "housing bubble" are sometimes used interchangeably.

Here, I am comparing Open and Closed Access ownership patterns as well as changes over time, from 2007 to 2014. Notice, in the Closed Access cities, middle and lower class households with mortgages owned about 9% of the housing stock. This is the portion of the population that was supposedly driving prices up. All mortgaged owner-occupiers only accounted for about 36% of Closed Access housing units. Even in other parts of the country they only accounted for about 42% of housing units. The difference is that in Closed Access cities, mortgaged homeowners overwhelmingly come from the top end of the income distribution.

It is implausible that working age, middle or lower income households were associated with significant pressures pushing Closed Access prices up. Non-conventional mortgages in Closed Access cities had to be focused on young households with high incomes.

In 2007, just under 9% and 17% of Closed and Open Access housing units were owned by households in the bottom 60% of incomes. By 2014, these numbers had dropped to just under 7% and 14%. So, about a quarter of the pool of working age, middle and lower class mortgaged homeowners had dried up since 2007. Homeownership rates have continued to fall since then.

In many ways, homeownership has collapsed much more than aggregate numbers would suggest. In Closed Access cities, mortgaged ownership is down to 30% of all households (from 36%). In Open Access areas, it's down to 34% (from 42%). In Open Access areas, about 40% of homeownership was unencumbered in 2007. By 2014, nearly half of owner-occupiers were unencumbered.

Total homeownership rates have been stabilized because unencumbered owners or lightly encumbered owners were not hurt as badly by falling equity and have been more likely to keep their homes. Mortgaged ownership has been devastated, both because existing owners were foreclosed on and because many potential new owners are locked out of the market.

* Contagion ownership patterns tend to be similar to Open Access ownership patterns.

**The systematic relative increase of low priced homes also began to appear in Washington, DC, Riverside, CA, and Miami by the end of the boom, because prices in their high end zip codes were rising above $500,000 where further home price appreciation slows down compared to lower price levels. This has nothing to do with credit access.

Tuesday, March 28, 2017

Housing: Part 214 - More Color on the real reason for price appreciation in "credit constrained" zip codes.

I have done some previous posts on the reason why low priced homes increased in value by more than high priced homes, in some cities. (Here's a post.) This had little or nothing to do with credit. It had to do with tax benefits.

Today, I will go into a little more detail to show how clear this pattern is.

I compared Seattle and Los Angeles in the previous post on this topic. Both cities had high expectations for future rent inflation at the height of the bubble in 2006. So, Price/Rent ratios at the top of the market were in the high 20s in both cities - far above the national norm. The difference between these cities is that rents aren't as high in Seattle as they are in Los Angeles, so home prices in absolute terms in Seattle are still somewhat lower. There are few zip codes in Seattle where the median home is worth more than $500,000. But, most of Los Angeles is above that price threshold.

This pattern of Price/Rent ratios exists in every MSA. Given that, and comparing White House tax numbers with BEA imputed rental income numbers (income tax benefits amount to about 25% of net rental yields after consumption of capital, and most of those benefits are claimed by high income households) we can infer that, at the low end of the market, dominated by landlord owners and by households with little in tax obligations, tax benefits are negligible. At the high end of the market, the marginal tax benefit must top out at something well above 30% of the value of net rental yield.

In 2006, low end Price/Rent levels appear to generally run about 30%-40% below P/R at the high end, across cities. Every city has a different peak Price/Rent level, depending on rent inflation expectations, property tax rates, etc. But, they all have this pattern. (Low end prices are currently more depressed than normal because of unusual credit constraints.)

But, it appears that at something around $500,000, the marginal tax benefit and the average tax benefit of any further increases in home value are about the same. Above that level, P/R flattens out. So, for cities where home prices rise above that level, this positive feedback loop in rising prices ceases. It isn't that low priced homes in Closed Access cities were rising unusually during the bubble. It's that their high end homes weren't rising as sharply as they would normally rise in a similar environment because their Price/Rent ratios were no longer expanding.

Here, we can see relative price levels, by price quintile, in Seattle and LA. None of the quintiles reached that price level in Seattle, so there was no difference in price appreciation between quintiles. In LA, all quintiles ended up generally above that price level, so each quintile moving up is more exposed to this cap in P/R inflation, and as you move up quintiles, price appreciation becomes more muted.

And, we can further confirm this pattern by looking at Riverside and San Francisco. By the end of the boom, the top quintiles in Riverside were just pushing above that $500,000 level. So, in Riverside, price appreciation in the top two quintiles is moderated, but the rest of the quintiles are still moving together. You can see a little bit of that pattern in Miami and Washington, DC, also.

In San Francisco, the top two quintiles began the period at or above that $500,000 range, and the rest of the quintiles moved above that range by the end of the boom. So, in San Francisco, we see the opposite pattern of Riverside. In San Francisco, the bottom three quintiles have different rates of appreciation, but the top two quintiles are similar to one another, because both of those quintiles started the period at peak P/R.

This pattern is quite regular.

Notice also what we see here. In the cities where low end prices

appreciated more, those prices collapsed early in the bust, along with the general price decline. It was natural to assume that this was a natural retraction of unsustainable demand. But, this was actually simply a reversal of this pattern, because now home prices were declining, so that the tax effect was creating a negative feedback loop in lower priced zip codes as they fell back below that $500,000 range.

And, we can confirm this, too, with a graph from another city - Phoenix. Is there anyone who will doubt that Phoenix was the poster child of a bubble, with free-flowing credit? But, Phoenix never pushed above that range. The top quintile of zip codes just barely reached above $500,000 at the peak. So, there was little difference among quintiles in Phoenix at the peak. And, until late 2008, there was little difference in the rate of decline.

So, there are two distinct reasons for the exceptional decline in low priced homes during the bust. The initial decline in 2007 and early 2008 was specific to the Closed Access cities and was simply an unwinding of this tax effect. Again, it isn't so much that the low tier homes were falling faster in those cities, as it is that the high tier homes had more moderate price shifts because they didn't have this pro-cyclical feedback. Notice how level the high quintile prices were in San Francisco and LA during the bust compared to the other cities listed here.

Then, there is a second wave of low tier price collapse after late 2008. This is especially noticeable in Phoenix and Seattle. We see this pattern in cities like St. Louis and Chicago, also. This is the period where federal public policy was devastating to the lower tier market. Fannie, Freddie, and Dodd-Frank have effectively shut down lending in the lower tier owner-occupier markets. I have been attributing most of the lower tier collapse to the GSEs, with a late assist from Dodd-Frank. But, looking at this next graph, and recognizing that the early collapse in first quintile prices in the Closed Access cities (and generally the excess gains in the Contagion and other cities, due to Riverside, Miami, and Washington) was due to the reversal of this tax effect, and not really due to credit contraction (relative to higher tiers of the market), Dodd-Frank appears to be a much stronger part of the late credit influence than I originally appreciated.

Notice that the lower tier collapse isn't as noticeable in the Closed Access cities as it is in the other cities during this later period. That is because these effects are now mitigating. All cities are affected by the severe constraints in low tier mortgage markets. But, in the Closed Access cities, as prices rise again, the positive feedback of P/R would be pushing those low priced homes up at a faster rate if it wasn't fighting those constraints.

I find that even I tend to make demand-side inferences that I eventually have to backtrack on when I realize that markets are more efficient and intrinsic value is more important than I gave them credit for. When I originally questioned the credit-supply explanation for this effect, I inferred from the pattern that it was the migration flows into and out of the Closed Access cities that created this effect. I inferred that the marginal home buyers had higher incomes than previous owners, so that they could capture more of these benefits, and that had something to do with the sharper rates of appreciation in lower priced neighborhoods.

But, I was wrong. Intrinsic value rules the day, in the end. In the aggregate, housing markets appear to be even more efficient than I tended to assume. There is ample inter-tier substitution throughout local housing markets. In hindsight, it is implausible that some portions of a metropolitan market would have unsustainably high valuations because of demand-side factors. (By this, I mean factors such as credit supply. Real estate will always be dominated by local factors that are related to changings rent levels due to localized market shifts in amenities, safety, etc.) In the aggregate, where those local valuation factors tend to average out, we can see that tax benefits are priced into home values quite systematically and the potency of credit supply as an explanation appears to be limited to the extreme case, where severe constraints prevent prices from rising to their intrinsic values. (Or, stated from a different framing, the retrenchment of the owner-occupier market farther up into mid-tier markets pulls prices in those markets down to the landlord level, where owner-occupier tax benefits are not available. So, the slope of the P/R relationship is now steeper.)

I suppose if I have changed my mind before, I might end up changing it again. But, so far, the changes induced by my exposure to the data have been changes toward more respect for macro-efficiency.

|

| idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com 2017 |

|

| idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com 2017 |

This pattern of Price/Rent ratios exists in every MSA. Given that, and comparing White House tax numbers with BEA imputed rental income numbers (income tax benefits amount to about 25% of net rental yields after consumption of capital, and most of those benefits are claimed by high income households) we can infer that, at the low end of the market, dominated by landlord owners and by households with little in tax obligations, tax benefits are negligible. At the high end of the market, the marginal tax benefit must top out at something well above 30% of the value of net rental yield.

In 2006, low end Price/Rent levels appear to generally run about 30%-40% below P/R at the high end, across cities. Every city has a different peak Price/Rent level, depending on rent inflation expectations, property tax rates, etc. But, they all have this pattern. (Low end prices are currently more depressed than normal because of unusual credit constraints.)

But, it appears that at something around $500,000, the marginal tax benefit and the average tax benefit of any further increases in home value are about the same. Above that level, P/R flattens out. So, for cities where home prices rise above that level, this positive feedback loop in rising prices ceases. It isn't that low priced homes in Closed Access cities were rising unusually during the bubble. It's that their high end homes weren't rising as sharply as they would normally rise in a similar environment because their Price/Rent ratios were no longer expanding.

|

| idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com 2017 |

|

| idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com 2017 |

|

| idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com 2017 |

This pattern is quite regular.

Notice also what we see here. In the cities where low end prices

|

| idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com 2017 |

|

| idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com 2017 |

So, there are two distinct reasons for the exceptional decline in low priced homes during the bust. The initial decline in 2007 and early 2008 was specific to the Closed Access cities and was simply an unwinding of this tax effect. Again, it isn't so much that the low tier homes were falling faster in those cities, as it is that the high tier homes had more moderate price shifts because they didn't have this pro-cyclical feedback. Notice how level the high quintile prices were in San Francisco and LA during the bust compared to the other cities listed here.

|

| idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com 2017 |

Notice that the lower tier collapse isn't as noticeable in the Closed Access cities as it is in the other cities during this later period. That is because these effects are now mitigating. All cities are affected by the severe constraints in low tier mortgage markets. But, in the Closed Access cities, as prices rise again, the positive feedback of P/R would be pushing those low priced homes up at a faster rate if it wasn't fighting those constraints.

I find that even I tend to make demand-side inferences that I eventually have to backtrack on when I realize that markets are more efficient and intrinsic value is more important than I gave them credit for. When I originally questioned the credit-supply explanation for this effect, I inferred from the pattern that it was the migration flows into and out of the Closed Access cities that created this effect. I inferred that the marginal home buyers had higher incomes than previous owners, so that they could capture more of these benefits, and that had something to do with the sharper rates of appreciation in lower priced neighborhoods.

But, I was wrong. Intrinsic value rules the day, in the end. In the aggregate, housing markets appear to be even more efficient than I tended to assume. There is ample inter-tier substitution throughout local housing markets. In hindsight, it is implausible that some portions of a metropolitan market would have unsustainably high valuations because of demand-side factors. (By this, I mean factors such as credit supply. Real estate will always be dominated by local factors that are related to changings rent levels due to localized market shifts in amenities, safety, etc.) In the aggregate, where those local valuation factors tend to average out, we can see that tax benefits are priced into home values quite systematically and the potency of credit supply as an explanation appears to be limited to the extreme case, where severe constraints prevent prices from rising to their intrinsic values. (Or, stated from a different framing, the retrenchment of the owner-occupier market farther up into mid-tier markets pulls prices in those markets down to the landlord level, where owner-occupier tax benefits are not available. So, the slope of the P/R relationship is now steeper.)

I suppose if I have changed my mind before, I might end up changing it again. But, so far, the changes induced by my exposure to the data have been changes toward more respect for macro-efficiency.

Monday, March 27, 2017

Stock picking vs. diversification

I've seen a lot of recent references to this great paper (pdf) from Hendrick Bessembinder at Arizona State. The paper notes that all of the net gains from equity ownership over time come from a very small sliver of the market. Most firms underperform over time.

Here is a graph from the paper.

There are two contrary conclusions we can reach from this. From the paper:

I wonder, for the non-diversified investor if the idea that there is a tradeoff between positive skew and average underperformance is necessarily true. It would depend on the balance between winners and losers. If an investor took a sort of barbell approach, only investing in equities with highly variable potential outcomes, it seems that there could be a large advantage created by that skew for portfolios that maintained positions without rebalancing. It would come down to skill, in the end. Small differences in the ability to pick winners - say, picking 60% winners instead of 40% - would make a huge difference in returns.

This seems like another piece of evidence that the real losers are the sort of reputation-based, semi-active portfolios that basically follow the indexes, with minor adjustments, or a sort of middle-of-the-road safe basket of tactical portfolio adjustments that are fairly conventional. These are the sorts of portfolios over time that tend to have net losses after costs. But, both fully passive and highly selective portfolios can do well. Fully passive is certainly recommended for most investors, but highly selective seems to be a reasonable choice, if the risks are known, with tremendous potential upside, and I suspect the benefits of that kind of portfolio tend to be underappreciated because it gets lumped in with "active" portfolios, which sophisticated observers who appreciate EMH are supposed to understand are a loser's bet.

Here is a graph from the paper.

There are two contrary conclusions we can reach from this. From the paper:

These results reaffirm the importance of portfolio diversification, particularly for those investors who view performance in terms of the mean and variance of portfolio returns...The results here show that underperformance can be anticipated more often than not for active managers with poorly diversified portfolios, even in the absence of costs, fees, or perverse skill.

At the same time, a preference for positive skewness in portfolio returns is not necessarily irrational, and it is known that diversification tends to eliminate skewness from portfolio returns. The results reported here also highlight the fact that poorly diversified portfolios occasionally deliver very large returns. As such, the results can justify a decision to not diversify by those investors who particularly value positive skewness in the distribution of possible investment returns, even in light of the knowledge that the undiversified portfolio will more likely underperform.The lesson for diversification is clear. But, it seems like there is an additional factor here having to do with rebalancing. For the fully diversified investor, rebalancing would be important - even a source of profit. But, for the less diversified investor, the positive skew would favor momentum.

I wonder, for the non-diversified investor if the idea that there is a tradeoff between positive skew and average underperformance is necessarily true. It would depend on the balance between winners and losers. If an investor took a sort of barbell approach, only investing in equities with highly variable potential outcomes, it seems that there could be a large advantage created by that skew for portfolios that maintained positions without rebalancing. It would come down to skill, in the end. Small differences in the ability to pick winners - say, picking 60% winners instead of 40% - would make a huge difference in returns.

This seems like another piece of evidence that the real losers are the sort of reputation-based, semi-active portfolios that basically follow the indexes, with minor adjustments, or a sort of middle-of-the-road safe basket of tactical portfolio adjustments that are fairly conventional. These are the sorts of portfolios over time that tend to have net losses after costs. But, both fully passive and highly selective portfolios can do well. Fully passive is certainly recommended for most investors, but highly selective seems to be a reasonable choice, if the risks are known, with tremendous potential upside, and I suspect the benefits of that kind of portfolio tend to be underappreciated because it gets lumped in with "active" portfolios, which sophisticated observers who appreciate EMH are supposed to understand are a loser's bet.

Wednesday, March 22, 2017

They terk our herms!

We now have a cosmopolitan version of "They terk er jerbs." "They terk our herms." Foreigners apparently have a strange affinity for buying homes only in cities with disastrously low levels of housing starts which leads to home prices well above replacement value. Strangely, foreigners apparently never want to buy homes in cities with healthy construction markets and high housing starts. There are never articles about the terrible problem of foreign home buyers in Houston. Surely, we can't trust people with such bizarre preferences.

The Economist takes note of this phenomenon. In the face of this trend, how can we possibly manage to create affordable housing for our own people?

Thursday, March 16, 2017

February 2017 Inflation

It looks like last month may have been a noise event. This month, shelter inflation tracks back up and non-shelter inflation tracks back down. Although, there is still a chance this is the beginning of an uptrend. The three month average non-shelter inflation rate is above 2%.

It looks like last month may have been a noise event. This month, shelter inflation tracks back up and non-shelter inflation tracks back down. Although, there is still a chance this is the beginning of an uptrend. The three month average non-shelter inflation rate is above 2%.Year-over-year CPI less food, energy, and shelter, remains 1.3%.

In real estate, I see some reports of positive activity, but bank lending has flat-lined. On the other hand, quarterly numbers for 2016 4Q flow of funds show mortgage lending continuing to accelerate. Is this because more lending is coming from non-bank sources, or is this because the flow of funds data is older, and it will show a slowdown in the first quarter?

In real estate, I see some reports of positive activity, but bank lending has flat-lined. On the other hand, quarterly numbers for 2016 4Q flow of funds show mortgage lending continuing to accelerate. Is this because more lending is coming from non-bank sources, or is this because the flow of funds data is older, and it will show a slowdown in the first quarter? The Federal Reserve report on Mortgage Debt Outstanding does appear to show a transition beginning from mortgages held at banks to mortgages originated through Fannie & Freddie. This is to be expected when short term rates are rising and the yield curve is flattening.

The Federal Reserve report on Mortgage Debt Outstanding does appear to show a transition beginning from mortgages held at banks to mortgages originated through Fannie & Freddie. This is to be expected when short term rates are rising and the yield curve is flattening. So, I suppose one question will be, can the GSEs create enough mortgage growth to overcome the decline in bank lending? It does appear that since mid-2016, there has been a loosening up of lending standards among conventional mortgages, so that there have been more mortgages with low down payments and more sales of existing homes at the low end of the market. This is a positive development. I suspect a good amount of healing, recovery, and price appreciation in those markets will need to happen before that leads to an increase in new housing starts in those markets. I suppose that means that the first result of any loosening will be healing of middle class balance sheets, and increases in the real housing stock which might reduce rent inflation would come later.

So, I suppose one question will be, can the GSEs create enough mortgage growth to overcome the decline in bank lending? It does appear that since mid-2016, there has been a loosening up of lending standards among conventional mortgages, so that there have been more mortgages with low down payments and more sales of existing homes at the low end of the market. This is a positive development. I suspect a good amount of healing, recovery, and price appreciation in those markets will need to happen before that leads to an increase in new housing starts in those markets. I suppose that means that the first result of any loosening will be healing of middle class balance sheets, and increases in the real housing stock which might reduce rent inflation would come later.Maybe we will see a bottom in the dropping homeownership rate, too, if Fannie & Freddie become more active. Here are the year-over-year and quarterly change in mortgages outstanding for 1-4 unit homes, for each conduit.

If Fannie and Freddie allow themselves to grow, it appears that they could counter the decline in bank lending.

If Fannie and Freddie allow themselves to grow, it appears that they could counter the decline in bank lending.PS. Notice in the YoY graph how the feds knocked the wind out of the GSEs when they took them over in 2008. Fortunately, GNMA took on some mortgage growth. In the end, I lay most of the defaults at the feet of federal management of the GSEs. They pulled the rug out from under the lower tier housing market after September 2008, and most of those defaults happened in 2009-2012. Maybe, finally, the GSEs will start to support that market again. Of course, the Fed is pulling against bank lending at the same time. Goodness help us if we ever manage to get all four cylinders running at the same time in the housing market. I suppose if that happened, I would recommend a long position in the laundry business. Somebody will need to clean all the bubble mongers' messed underpants.

Tuesday, March 14, 2017

Housing: Part 213 - Seattle makes a bid for Closed Access status

Seattle has apparently passed a law that intends to force landlords to rent to qualified tenants on a first-come, first-served basis. The point is to avoid discrimination, but I would expect many small single family residence landlords to bail or work around this. Most small scale landlords I know seem to have their own idiosyncratic systems for finding quality tenants, which they consider part of their competitive advantage.

It seems like this will surely increase rents. That would normally drive more tenants to ownership, but since we have implemented non-monetary obstacles to ownership, I'm not sure how much of a shift could happen in the current regime.

Looks like landlords will be taking an even larger risk premium than they currently do.

PS. This reminds me of the New Deal's NIRA, as described by Amity Shlaes in The Forgotten Man.

It seems like this will surely increase rents. That would normally drive more tenants to ownership, but since we have implemented non-monetary obstacles to ownership, I'm not sure how much of a shift could happen in the current regime.

Looks like landlords will be taking an even larger risk premium than they currently do.

PS. This reminds me of the New Deal's NIRA, as described by Amity Shlaes in The Forgotten Man.

Monday, March 13, 2017

Housing: Part 212 - Consumption from home equity.

A broadly held concern about rising home prices is that rising prices fuel unsustainable consumption spending when households tap home equity to spend more. Here is a new article on the subject in Australia (HT: John Wake). The article mentions research that claims 24% of each dollar in capital gains are taken by owners in new debt. This is similar to an estimate by Mian and Sufi.

I think, on this topic, it is important to distinguish between real (making stuff) and nominal (exchanging money for stuff) economic activity. This is purely a nominal issue. So, I think instead of framing this as an issue of households overconsuming in an unsustainable way, it is more accurate to say that, of the stuff we were making, real estate beneficiaries were claiming more of it, at the expense of people who were producing stuff. That should be inflationary. And, if it is not, then it means that the central bank is counteracting the phenomenon with tight money.

Whatever the inflation effect, real estate owners were consuming, in the real sense, at the expense of producers.

The research referenced in the article also mentions that real estate gains draw some owners out of the labor force because of their newfound wealth. This makes sense. But, again, thinking about this in terms of real economic claims on production, we might expect a similar rise in labor force participation among producers whose incomes are now vying for a smaller portion of production.

In fact, during the housing "bubble", labor force participation was quite strong. I have done a lot of work on this blog in the past showing how demographics are responsible for much of the drop in labor force participation, recently. Here, just as a quick and dirty way to try to control for that, I am using prime age male labor force participation. There is a long term downtrend, but after we account for that, we can see that labor force participation was strong.

This makes sense to me, because I don't think credit supply or irrational speculation have much to do with the housing "bubble". I think it mostly had to do with high skilled working people buying access into the Closed Access labor markets where limited housing serves as a gatekeeper. So, there while there was certainly some amount of typical labor force reductions because of capital gains, many of the households utilizing gains from those homes for consumption were in those homes specifically to work.

In any case, I don't see much cause for even bringing the central bank into this. From the point of view of consumers who don't have access to these capital gains, this seems like a real shock. There is less production for them to claim. That is going to be the case regardless of the inflation rate. Monetary policy can't solve the problem of unsustainable consumption, even if that is what is happening.

But, households can't unsustainably consume, domestically. They can only change their relative claims on existing production. Here, the trade deficit seems to suggest unsustainability. In effect, foreign capital was flooding into our capital markets, helping to push up home prices, so that, in effect, we were borrowing from foreigners in order to buy production from foreigners, and this is why it was unsustainable.

And, this is why a clear understanding of what has been happening in foreign trade and investment is key. It is true that the trade deficit ballooned during the housing "bubble" as foreign investment flooded into the US. But, at the same time, US net income on foreign investment was also strong and positive. If we were hawking our futures for unsustainable consumption, then our net foreign income should have dropped as foreign savers claimed their profits from our borrowing. Considering the significant spike in net imports, this should be a shocking piece of evidence.

The explanation for this is that the causation goes the other way. Closed Access exclusion supports excessive wages and profits in the Closed Access cities. Many of those profits are earned overseas. Those Closed Access incomes were the cause of high home prices, the cause of rising foreign income, and the cause of foreign capital inflows. And, they funded those imports. Even with the continued high trade deficit, net foreign income for US savers is high.

Yet, again, whether this consumption was sustainable or not, what does the central bank have to do with it? That will be the case regardless of the rate of inflation. The only way for monetary policy to cut into this consumption is to create a real shock large enough to induce retrenchment. This is basically what we did.

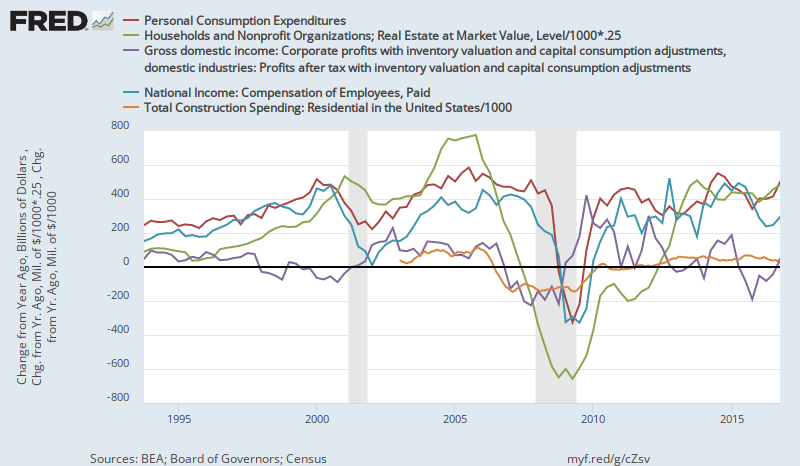

Here is a graph of the year-over-year growth in personal consumption expenditures (red). I have also included the growth in mortgages outstanding, then I deducted residential investment in single family structures to estimate the amount of new mortgages that were coming out of capital gains on existing housing units (blue). I also include a measure of one quarter of the increase in the value of existing real estate, to estimate the amount of capital gains that are claimed by owners for consumption.

For the period from 2001 to 2006, this growth in mortgage credit accounts for the entire growth in PCE. Might it have been the case that homeowners with windfall gains were claiming all of the marginal new consumption since 2001? Could it be that producers (workers and investors) didn't increase their consumption at all - even in nominal terms - during the housing boom? Could it be that they were working harder just so they could produce more for the housing windfall spenders?*

Mian & Sufi do estimate that 2.8% of GDP was funded by home equity borrowing every year from 2002 to 2006. That's enough to cover the growth in personal consumption expenditures shown above.

Again, short of causing a real shock to incomes, I'm not sure what monetary policy could do about this. A rise or drop in inflation would have presumably increased or decreased nominal spending from both the windfall spenders and producers.

As we can see in the graph, real estate values were the first thing to stop expanding. We might expect some stickiness in the willingness of households to continue tapping home equity for consumption. So, mortgage expansion continued until early 2008. And, PCE growth continued to expand along with mortgage growth. So, for most of 2006 and 2007, marginal new consumption was still being claimed by homeowners, but now it was coming at the expense of home equity.

But, as I have documented, at this point, much of this equity harvesting wasn't from continuing homeowners. There was a spike of selling out of homeownership. The homeownership rate was declining, even though the natural inflow of first time buyers tends to be fairly stable. This meant that housing starts were collapsing and the typical owner of the housing stock was becoming more leveraged, just because long time owners were being replaced by new owners. We can see this where total growth in gross mortgages outstanding was dropping much faster than mortgages outstanding net of new investment.

Here is a similar graph, but here, I have added annualized residential investment and year-over-year growth in compensation and after tax domestic corporate profit. Here, notice that growth in compensation also nearly adds up to the growth in PCE. So, between the growth in mortgages and the growth in compensation, consumption is more than accounted for.

This is because much of that mortgage growth and consumption growth was funding savings. The way it was funding savings was that first time homebuyers were buying homes from long term homeowners who were exiting homeownership. This created significant new mortgage debt. But, the former home equity of those former home owners wasn't being consumed. It was being saved. Much of it was funding CDOs. This didn't show up as savings, because we don't tend to count capital gains as savings. But, there was a lot of savings flowing out of home equity and into fixed income securities.

Notice that compensation and PCE dropped together in 2008 about when mortgage growth dropped. Mortgage growth dropped after the private securitization market collapsed in summer 2007. At that point, a financial crisis had begun to build, and the Fed was making emergency loans to troubled financial firms. From summer 2007 until they were running out of treasuries to sell in September 2008, they were "sterilizing" those loans. In other words, they were trying to save banks without actually injecting cash into the economy.

But, if consumption was being facilitated by real estate gains and expanding mortgages, then really, from 2004 to 2007, the Fed had already been sort of sterilizing the money supply, sucking out currency to make up for the extra consumption that was funded by real estate gains. When the private securitization market collapsed, if estimates of homeowner debt utilization are accurate, then when the Fed was sterilizing their emergency loans in order to avoid providing money to the economy, they should have been shoveling massive amounts of cash into the economy to make up for the drop in nominal spending.

It isn't the Fed's job to impose a negative shock to make up for past consumption. It's the Fed's job to provide stability. In fact, I submit that the Fed should have been providing more accommodation back in 2006 when home equity started to dive. This sharp increase in homeowner leverage was already a sign of dislocation. We can see in the graph above that, while compensation didn't suffer much from that dislocation, domestic corporate profits did. And, we can see the drop in domestic corporate profits was largely due to the collapse in residential investment.

The country thought the trade deficit was unsustainable, residential investment was unsustainable, and home prices were unsustainable, all funded by foreign capital. We were wrong on all counts.

So what kept us afloat between 2006-2008? Those foreign profits. Here is a chart of US corporate foreign profits as a percentage of GDP.

________________

* This transfer of consumption is accounted for, to a certain extent by the high incomes of Closed Access producers. The high incomes of Closed Access workers and firms mean that production from Closed Access industries is more expensive - there is less consumer surplus from those industries. So, some of the reduced real consumption is from producers in the rest of the country, who pay more for Closed Access output. Some of the reduced real consumption is from producers in the Closed Access cities who pay more for housing, leaving less of their incomes for other consumption.

I think, on this topic, it is important to distinguish between real (making stuff) and nominal (exchanging money for stuff) economic activity. This is purely a nominal issue. So, I think instead of framing this as an issue of households overconsuming in an unsustainable way, it is more accurate to say that, of the stuff we were making, real estate beneficiaries were claiming more of it, at the expense of people who were producing stuff. That should be inflationary. And, if it is not, then it means that the central bank is counteracting the phenomenon with tight money.

Whatever the inflation effect, real estate owners were consuming, in the real sense, at the expense of producers.

The research referenced in the article also mentions that real estate gains draw some owners out of the labor force because of their newfound wealth. This makes sense. But, again, thinking about this in terms of real economic claims on production, we might expect a similar rise in labor force participation among producers whose incomes are now vying for a smaller portion of production.

|

| Source |

This makes sense to me, because I don't think credit supply or irrational speculation have much to do with the housing "bubble". I think it mostly had to do with high skilled working people buying access into the Closed Access labor markets where limited housing serves as a gatekeeper. So, there while there was certainly some amount of typical labor force reductions because of capital gains, many of the households utilizing gains from those homes for consumption were in those homes specifically to work.

In any case, I don't see much cause for even bringing the central bank into this. From the point of view of consumers who don't have access to these capital gains, this seems like a real shock. There is less production for them to claim. That is going to be the case regardless of the inflation rate. Monetary policy can't solve the problem of unsustainable consumption, even if that is what is happening.

But, households can't unsustainably consume, domestically. They can only change their relative claims on existing production. Here, the trade deficit seems to suggest unsustainability. In effect, foreign capital was flooding into our capital markets, helping to push up home prices, so that, in effect, we were borrowing from foreigners in order to buy production from foreigners, and this is why it was unsustainable.

And, this is why a clear understanding of what has been happening in foreign trade and investment is key. It is true that the trade deficit ballooned during the housing "bubble" as foreign investment flooded into the US. But, at the same time, US net income on foreign investment was also strong and positive. If we were hawking our futures for unsustainable consumption, then our net foreign income should have dropped as foreign savers claimed their profits from our borrowing. Considering the significant spike in net imports, this should be a shocking piece of evidence.

|

| Source |

Yet, again, whether this consumption was sustainable or not, what does the central bank have to do with it? That will be the case regardless of the rate of inflation. The only way for monetary policy to cut into this consumption is to create a real shock large enough to induce retrenchment. This is basically what we did.

|

| Source |

For the period from 2001 to 2006, this growth in mortgage credit accounts for the entire growth in PCE. Might it have been the case that homeowners with windfall gains were claiming all of the marginal new consumption since 2001? Could it be that producers (workers and investors) didn't increase their consumption at all - even in nominal terms - during the housing boom? Could it be that they were working harder just so they could produce more for the housing windfall spenders?*

Mian & Sufi do estimate that 2.8% of GDP was funded by home equity borrowing every year from 2002 to 2006. That's enough to cover the growth in personal consumption expenditures shown above.

Again, short of causing a real shock to incomes, I'm not sure what monetary policy could do about this. A rise or drop in inflation would have presumably increased or decreased nominal spending from both the windfall spenders and producers.

As we can see in the graph, real estate values were the first thing to stop expanding. We might expect some stickiness in the willingness of households to continue tapping home equity for consumption. So, mortgage expansion continued until early 2008. And, PCE growth continued to expand along with mortgage growth. So, for most of 2006 and 2007, marginal new consumption was still being claimed by homeowners, but now it was coming at the expense of home equity.

But, as I have documented, at this point, much of this equity harvesting wasn't from continuing homeowners. There was a spike of selling out of homeownership. The homeownership rate was declining, even though the natural inflow of first time buyers tends to be fairly stable. This meant that housing starts were collapsing and the typical owner of the housing stock was becoming more leveraged, just because long time owners were being replaced by new owners. We can see this where total growth in gross mortgages outstanding was dropping much faster than mortgages outstanding net of new investment.

Here is a similar graph, but here, I have added annualized residential investment and year-over-year growth in compensation and after tax domestic corporate profit. Here, notice that growth in compensation also nearly adds up to the growth in PCE. So, between the growth in mortgages and the growth in compensation, consumption is more than accounted for.

This is because much of that mortgage growth and consumption growth was funding savings. The way it was funding savings was that first time homebuyers were buying homes from long term homeowners who were exiting homeownership. This created significant new mortgage debt. But, the former home equity of those former home owners wasn't being consumed. It was being saved. Much of it was funding CDOs. This didn't show up as savings, because we don't tend to count capital gains as savings. But, there was a lot of savings flowing out of home equity and into fixed income securities.

Notice that compensation and PCE dropped together in 2008 about when mortgage growth dropped. Mortgage growth dropped after the private securitization market collapsed in summer 2007. At that point, a financial crisis had begun to build, and the Fed was making emergency loans to troubled financial firms. From summer 2007 until they were running out of treasuries to sell in September 2008, they were "sterilizing" those loans. In other words, they were trying to save banks without actually injecting cash into the economy.

But, if consumption was being facilitated by real estate gains and expanding mortgages, then really, from 2004 to 2007, the Fed had already been sort of sterilizing the money supply, sucking out currency to make up for the extra consumption that was funded by real estate gains. When the private securitization market collapsed, if estimates of homeowner debt utilization are accurate, then when the Fed was sterilizing their emergency loans in order to avoid providing money to the economy, they should have been shoveling massive amounts of cash into the economy to make up for the drop in nominal spending.

It isn't the Fed's job to impose a negative shock to make up for past consumption. It's the Fed's job to provide stability. In fact, I submit that the Fed should have been providing more accommodation back in 2006 when home equity started to dive. This sharp increase in homeowner leverage was already a sign of dislocation. We can see in the graph above that, while compensation didn't suffer much from that dislocation, domestic corporate profits did. And, we can see the drop in domestic corporate profits was largely due to the collapse in residential investment.

|

| Source |

So what kept us afloat between 2006-2008? Those foreign profits. Here is a chart of US corporate foreign profits as a percentage of GDP.

________________

* This transfer of consumption is accounted for, to a certain extent by the high incomes of Closed Access producers. The high incomes of Closed Access workers and firms mean that production from Closed Access industries is more expensive - there is less consumer surplus from those industries. So, some of the reduced real consumption is from producers in the rest of the country, who pay more for Closed Access output. Some of the reduced real consumption is from producers in the Closed Access cities who pay more for housing, leaving less of their incomes for other consumption.

Friday, March 10, 2017

Cyclical Mixed Signals

I have become fairly bearish. I think unfounded fears about "asset prices" and a bifurcation between returns on real estate vs. returns on fixed income is pulling the Fed to a position that is too hawkish with rate expectations that are too high. Stagnating growth in debt is a really bad sign when, given the current economic fundamentals, mortgage debt levels are far too low.

That being said, the employment flows data is looking pretty upbeat. Flows from unemployed to employed have recovered quite nicely. And, I must admit that flows look a lot like 1999, when the Fed was raising rates, but economic expansion was pulling economic growth along, and long term rates were rising right along with short term rates.

That being said, the employment flows data is looking pretty upbeat. Flows from unemployed to employed have recovered quite nicely. And, I must admit that flows look a lot like 1999, when the Fed was raising rates, but economic expansion was pulling economic growth along, and long term rates were rising right along with short term rates.

Eventually, long term rates reversed and a correction followed in 2000. So, I think the direction of long term rates is a decent bellwether of the direction of economic activity. And, this has been mixed lately too, with rates rising late last year and then generally levelling off. The sharp rise in sentiment in several surveys can't be ignored.

So, it seems we remain in a holding pattern. I don't think that the risk/reward of positioning for a contraction is worth it, and it still seems too early to commit to positions that will gain from falling interest rates or from an eventual rebound. It would be highly unusual at this point, I think, to see multi-year double-digit equity gains. So, I don't see a lot of risk with being defensive. I suppose there are idiosyncratic plays that will perform well, but this seems like a time where dry powder has its own value.

I haven't touched on unemployment duration data for a while. Long duration unemployment continues to slowly recede, providing some ammunition for continued extra growth potential. Before the Great Recession, we might have expected long term unemployment to be at about 1.2 million now, instead of 1.8 million. Inferring from the BLS's median and average duration statistics, it seems as though that is basically where we stand now. There are probably about 1.2 million workers who have been unemployed for longer than 26 weeks, who are re-entering the labor force at a typical rate. Then, there are about 600,000 unemployed workers who have been unemployed for a very long time - more than 18 months, typically - who still identify as unemployed and in the labor force. I wonder how much of that is related to the continued depression level residential construction activity. I don't see a groundswell of support for solving that problem, so if that is the cause of the persistent long term UE problem, then it probably isn't going away in any case.

I haven't touched on unemployment duration data for a while. Long duration unemployment continues to slowly recede, providing some ammunition for continued extra growth potential. Before the Great Recession, we might have expected long term unemployment to be at about 1.2 million now, instead of 1.8 million. Inferring from the BLS's median and average duration statistics, it seems as though that is basically where we stand now. There are probably about 1.2 million workers who have been unemployed for longer than 26 weeks, who are re-entering the labor force at a typical rate. Then, there are about 600,000 unemployed workers who have been unemployed for a very long time - more than 18 months, typically - who still identify as unemployed and in the labor force. I wonder how much of that is related to the continued depression level residential construction activity. I don't see a groundswell of support for solving that problem, so if that is the cause of the persistent long term UE problem, then it probably isn't going away in any case.

So, we seem to be at "full employment", with a persistent long term unemployed population that continues to decline at maybe 100,000 to 200,000 per year. I'm not sure if that is enough of a boost to employment growth to make much difference.

Mixed signals again.

That being said, the employment flows data is looking pretty upbeat. Flows from unemployed to employed have recovered quite nicely. And, I must admit that flows look a lot like 1999, when the Fed was raising rates, but economic expansion was pulling economic growth along, and long term rates were rising right along with short term rates.

That being said, the employment flows data is looking pretty upbeat. Flows from unemployed to employed have recovered quite nicely. And, I must admit that flows look a lot like 1999, when the Fed was raising rates, but economic expansion was pulling economic growth along, and long term rates were rising right along with short term rates.Eventually, long term rates reversed and a correction followed in 2000. So, I think the direction of long term rates is a decent bellwether of the direction of economic activity. And, this has been mixed lately too, with rates rising late last year and then generally levelling off. The sharp rise in sentiment in several surveys can't be ignored.

So, it seems we remain in a holding pattern. I don't think that the risk/reward of positioning for a contraction is worth it, and it still seems too early to commit to positions that will gain from falling interest rates or from an eventual rebound. It would be highly unusual at this point, I think, to see multi-year double-digit equity gains. So, I don't see a lot of risk with being defensive. I suppose there are idiosyncratic plays that will perform well, but this seems like a time where dry powder has its own value.

I haven't touched on unemployment duration data for a while. Long duration unemployment continues to slowly recede, providing some ammunition for continued extra growth potential. Before the Great Recession, we might have expected long term unemployment to be at about 1.2 million now, instead of 1.8 million. Inferring from the BLS's median and average duration statistics, it seems as though that is basically where we stand now. There are probably about 1.2 million workers who have been unemployed for longer than 26 weeks, who are re-entering the labor force at a typical rate. Then, there are about 600,000 unemployed workers who have been unemployed for a very long time - more than 18 months, typically - who still identify as unemployed and in the labor force. I wonder how much of that is related to the continued depression level residential construction activity. I don't see a groundswell of support for solving that problem, so if that is the cause of the persistent long term UE problem, then it probably isn't going away in any case.

I haven't touched on unemployment duration data for a while. Long duration unemployment continues to slowly recede, providing some ammunition for continued extra growth potential. Before the Great Recession, we might have expected long term unemployment to be at about 1.2 million now, instead of 1.8 million. Inferring from the BLS's median and average duration statistics, it seems as though that is basically where we stand now. There are probably about 1.2 million workers who have been unemployed for longer than 26 weeks, who are re-entering the labor force at a typical rate. Then, there are about 600,000 unemployed workers who have been unemployed for a very long time - more than 18 months, typically - who still identify as unemployed and in the labor force. I wonder how much of that is related to the continued depression level residential construction activity. I don't see a groundswell of support for solving that problem, so if that is the cause of the persistent long term UE problem, then it probably isn't going away in any case.So, we seem to be at "full employment", with a persistent long term unemployed population that continues to decline at maybe 100,000 to 200,000 per year. I'm not sure if that is enough of a boost to employment growth to make much difference.

Mixed signals again.

Wednesday, March 8, 2017

Housing: Part 211 - Measures of savings and credit supply

In a recent profile of Amir Sufi (HT: John Wake):

I can see how he arrives at this conclusion. But, my question is, where did that credit come from? Lenders can't conjure up capital out of thin air. For interest rates to have been low, savings needed to be strong.

Measures of savings tend to show low savings rates at the time. Capital gains aren't included in savings rates, though. In the graph here, home values are inverted. Notice that savings moves up when home prices move down and vice versa. This is normally treated as a source of unsustainable consumption, but in this case, that is not necessarily true. (1) The gains were largely gains in Closed Access real estate, which are permanent gains until a sea change happens in urban governance, and are certainly permanent for households that sell and realize capital gains. (2) During this time, there appears to have been a significant amount of harvesting of real estate capital gains which were then transferred into savings instead of into consumption. This combination of factors explains why interest rates were low while savings was low and credit levels were spiking. Sufi is right that credit demand wasn't particularly high. This is further confirmed by the declining rate of homeownership at the height of the housing boom.

In a way, I think Sufi's comment here gets halfway to a contrarian point of view regarding credit and business cycles. There is an element of Scott Sumner's reasoning from a price change here. Let's call it reasoning from a credit quantity. As Sufi notes, credit levels could rise because of rising demand or rising supply. The rise in debt leading to a financial downturn is usually presented as if it is from demand. But, this seems wrong to me. Usually, it is associated with a rise in mortgage debt. In this recent case, mortgage debt was clearly associated with two factors:

1) Closed Access home values, which reflect an arbitrary limit on productivity, and thus would be associated with declining economic expectations.

and

2) Low real interest rates, which are usually also associated with declining sentiment.

Yet, these trends in debt are usually treated as bouts of risk taking and exuberance that are unsustainable - inevitably leading to a bust. Shouldn't we treat these periods of rising debt levels as the first signs of a downturn in sentiment, not as naïve exuberance?

Sufi emphasized that the debt run-up resulted from a positive credit supply shock—not a sudden demand for more credit. Credit supply shocks occur when lenders decide to offer more loans based on “reasons unrelated to actual underlying performance of companies or the income of households.” Because these spikes occur when interest rates are low, Sufi rules out increased credit demand as a factor. If lenders were reluctant to expand credit supply, interest rates would have risen.

|

| Source |

Measures of savings tend to show low savings rates at the time. Capital gains aren't included in savings rates, though. In the graph here, home values are inverted. Notice that savings moves up when home prices move down and vice versa. This is normally treated as a source of unsustainable consumption, but in this case, that is not necessarily true. (1) The gains were largely gains in Closed Access real estate, which are permanent gains until a sea change happens in urban governance, and are certainly permanent for households that sell and realize capital gains. (2) During this time, there appears to have been a significant amount of harvesting of real estate capital gains which were then transferred into savings instead of into consumption. This combination of factors explains why interest rates were low while savings was low and credit levels were spiking. Sufi is right that credit demand wasn't particularly high. This is further confirmed by the declining rate of homeownership at the height of the housing boom.

In a way, I think Sufi's comment here gets halfway to a contrarian point of view regarding credit and business cycles. There is an element of Scott Sumner's reasoning from a price change here. Let's call it reasoning from a credit quantity. As Sufi notes, credit levels could rise because of rising demand or rising supply. The rise in debt leading to a financial downturn is usually presented as if it is from demand. But, this seems wrong to me. Usually, it is associated with a rise in mortgage debt. In this recent case, mortgage debt was clearly associated with two factors:

1) Closed Access home values, which reflect an arbitrary limit on productivity, and thus would be associated with declining economic expectations.

and

2) Low real interest rates, which are usually also associated with declining sentiment.

Yet, these trends in debt are usually treated as bouts of risk taking and exuberance that are unsustainable - inevitably leading to a bust. Shouldn't we treat these periods of rising debt levels as the first signs of a downturn in sentiment, not as naïve exuberance?

Monday, March 6, 2017

Housing: Part 210 - Credit and Home Prices

There were a handful of cities where home prices rose especially sharply and where home prices at the low end rose significantly more than at the high end during the boom. This has been widely attributed to credit access to marginal households.